Sarai (or Sarah)

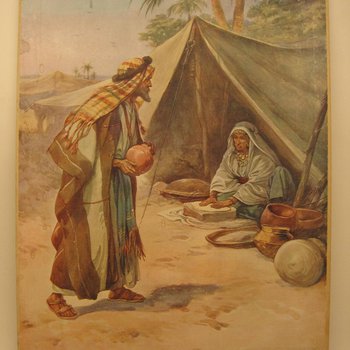

The “birth” of Judaism (and Islam) is actually a story about the intertwining lives of two Ancient Mothers: Sarai and Hagar. Sarai, or “the princess,” was the half-sister and wife to Abraham, patriarch and Ancient Founding Father of Judaism (Genesis 20:12). Sarai is the most well-known Ancient Mother of Judaism and her marital rank marks an important cultural aspect of ancient Hebrew life because it demonstrated Sarai’s elevated status. It could also imply her role as a priestess in accordance with the ancient Mesopotamian culture and traditions she most likely was born into and how Hagar, an Egyptian princess, became Sarai’s shifhah or, roughly translated, owned companion / handmaid (Teubal, 1984: 1990). Scripture notes that Sarai acquired Hagar after Sarai herself had been brought to Egypt to be a slave-concubine in the house of the Pharaoh until God intervened and Pharaoh released Sarai, but not before bestowing a large quantity of gifts upon her, including Hagar (Genesis 12).

Following this narrative, Sarai and Hagar and Abraham traveled together for approximately ten years before the question of children (or heirs) arose (Teubal, 1990). Hebrew Scripture states that Sarai was unable to bear children herself, although controversy exists as to whether this implies that Sarai was literally unable to become pregnant or if it was a socio-cultural description of her possible status as a priestess-wife in which she was forbidden to become pregnant (Teubal, 1984; 1990). Regardless, Sarai proposed a surrogate solution: that Abraham have intercourse with Hagar so that Hagar could bring forth a child for Sarai to claim as her own (Frymer-Kensky, 2002; Genesis 16:2; Teubal, 1990). Bloodlines were traced through the mother in the ancient Mesopotamian culture of Sarai and the ancient Egyptian culture of Hagar which meant that having children ensured the preservation of culture, the family unit, and the woman’s lineage (Frymer-Kensky, 2002; Teubal, 1990). Having a subordinate serve as a surrogate mother was a practice sometimes utilized in ancient civilizations and this process was controlled by the higher-ranking woman, not by her husband (Frymer-Kensky, 2002; Teubal, 1990).

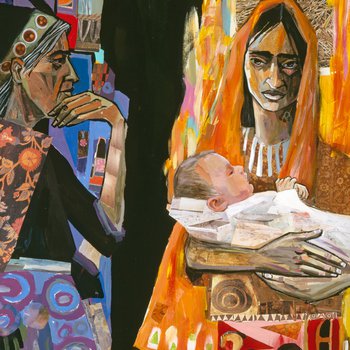

Hagar and Abraham fulfilled Sarai's request which quickly led to Hagar becoming pregnant. Tensions rose in this new situation, however, as Hagar felt more empowered when she was with child and regarded Sarai as more of an equal rather than as her superior (Frymer-Kensky, 2002; Genesis 15:3-6; Teubal, 1984; 1990). Since becoming a mother marked a woman’s foothold in maintaining her cultural honor and security, it wasn’t uncommon for the primary wife to take measures to ensure her domestic power was not usurped (Bird, 1974; Teubal, 1990; Trible, 2003). This was true for Sarai who first became angry at Abraham, whom she believed had encouraged Hagar’s disregard for her, and then Sarai took measures to reassert her authority over Hagar (Frymer-Kensky, 2002; Genesis 15:3-6; Teubal, 1990). Hagar rejected Sarai’s attempt to re-establish her superior status and left the tent of Sarai, only to have a spiritual intercession with God who told her to return to Sarai (Frymer-Kensky, 2002; Genesis 15:3-6; 16:7-14; Teubal, 1990). Hagar returns and gives birth to Ishmael, although conflicting theories exist as to who Ishmael is considered an heir to: Sarai or Abraham?

Several years later another very interesting event occurred. Genesis 18 recounts that Abraham and Sarai receive travelers into their dwelling, one of whom was God in disguise. During this time God enters into a covenant with Sarai promising her that, despite her advanced age, she will become a birth mother of a great patriarch. Sarai privately laughs at that thought but God then asks why she laughed. It is during this interaction that Sarai accepts divine intervention (and religious conversion) and it comes to pass that she births a son, Issac (Genesis, 18; Teubal, 1990). The arrival of Issac, however, challenges the existing “heir” situation with Ishmael in terms of inheritance so Sarai rejects Ishmael as an heir and, according to the Hebrew narrative, Hagar and Ishmael are forced to leave (Frymer-Kensky, 2002; Genesis 21:8-13). Their departure ensures two things: that they are granted their freedom and that Ishmael is no longer eligible for an inheritance (Teubal, 1984).

Yet this is not the end of Sarai’s story nor of Hagar’s.* For Sarai, God fulfilled the promise that she would become a mother of one of God’s chosen patriarchs, Isaac, and, with this event, Sarai’s roles as primary wife and mother to the Hebrew/Jewish nation brought forth by Isaac’s descendants affirmed the existing cultural framework for ancient Jewish women. But perhaps even more importantly, this event marked Sarai as a prominent female historical figure in a covenant with God in her own right (Young, 2013). As a matriarch, Sarai’s story exemplifies the importance of women in religious accounts and exemplifies “the strength and courage of God’s chosen agents'' (Stowasser, 1994). Neither Judaism nor Islam would have been established without Sarai.

(*See the “Ancient Mothers of Islam” for more about Hagar’s story)

Works Cited

Bird, P. (1974). Images of women in the Old Testament. In Ruether, R. R. (Ed.), Religion and Sexism: Images of Women in the Jewish and Christian Traditions (pp.41-88). New York, NY: Simon and Schuster.

Frymer-Kensky, T. (2002). Reading the Women of the Bible: A New Interpretation of their

Stories. New York, NY: Schocken Books.

Stowasser, B.F. (1994). Women in the Qur’an, Traditions, and Interpretations. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Teubal, S. J. (1984). Sarah the Priestess: The First Matriarch of Genesis. Athens, OH: Swallow Press.

Teubal, S. J. (1990). The Lost Tradition of the Matriarchs: Hagar the Egyptian. New York, NY: Harper & Row, Publishers, Inc.

Trible, P. (2003). Genesis 22: The sacrifice of Sarah. In J. M. Soskice, & D. Lipton (Eds.),

Feminism and Theology (pp. 144-154). New York, NY: Oxford University Press, Inc. Young, S. (Ed.). (1993). An Anthology of Sacred Texts by and about Women. New York, NY:

The Crossroad Publishing Company.